![]() This is part of a series of stories in which the ABC15 Investigators and the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting collaborated to explore how Arizona regulates the storage and transportation of hazardous chemicals across the state.

This is part of a series of stories in which the ABC15 Investigators and the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting collaborated to explore how Arizona regulates the storage and transportation of hazardous chemicals across the state.

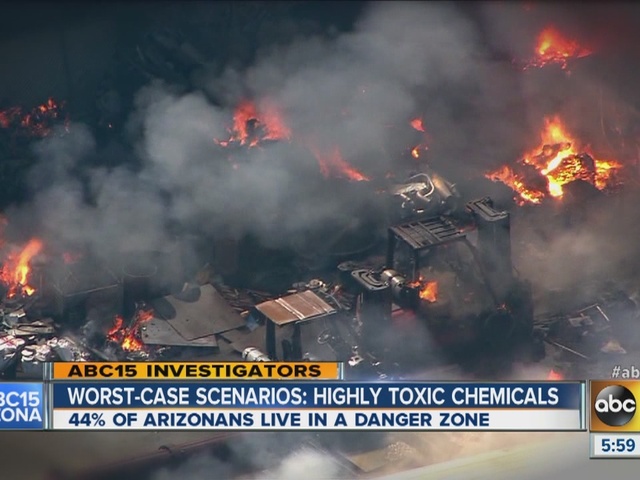

More than 2.8 million Arizona residents -- or 44 percent of the state's population -- live within areas that are most vulnerable to a catastrophic accidental release of gaseous, and sometimes explosive hazardous chemicals.

The toxic agents, which the Environmental Protection Agency deems extremely hazardous, include chemicals such as anhydrous ammonia, chlorine and hydrofluoric acid. They are stored in more than 100 facilities that dot the Arizona landscape and, when released, can cause temporary blindness, searing pain, suffocation, and even death.

The radius of these danger zones can reach up to 22 miles from the center of the incident. They include clouds of toxic gases or explosions from flammable materials in the worst possible accident scenarios at Arizona facilities designated by the EPA as a serious risk to residential populations.

Use the interactive maps below to find the danger zones in your area.Click the center of the circle for details about the facility in your neighborhood.

WORST-CASE SCENARIO: TOXIC CHEMICALS

WORST-CASE SCENARIO: FLAMMABLE CHEMICALS

The "worst-case" scenarios are part of the EPA's Risk Management Plan (RMP) law, which requires facilities storing large amounts of hazardous materials to file the plans for emergency planning and risk assessment purposes. The companies include water treatment plants, grocery store distribution centers and commonly known businesses such as Target, Wal-Mart and Shamrock Farms.

The EPA is tasked with collecting and maintaining these records, but a patchwork of state and federal regulations make it unclear whether the plans are effective in protecting surrounding communities, the ABC15 Investigators and the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting found through a months-long analysis of federal records.

%page_break%

Toxic and flammable worst-case scenarios limited in scope

The information within RMPs limits emergency planning because the worst-case scenarios only describe leaks from the largest containers of specific chemicals that exceed storage thresholds. It doesn't take into account the proximity of other containers storing the same chemical, the total amount of all chemicals stored at the facility, or the combination of different chemicals at that location.

The plans also fail to determine realistic estimates of residential populations surrounding these facilities. The estimates don't include employees within the company or the schools, hospitals, businesses and transportation routes nearby.

And it's unclear whether facilities importing these chemicals are following RMP laws. One Arizona facility was mentioned, but not identified, in a recent EPA Office of Inspector General (OIG) report that questioned whether that facility was reporting its chemical imports. According to the OIG opinion, the chemicals weren't identified on the company's current RMP documents.

The report also stated that between October 2008 and March 2012, 460 accidents were reported to the EPA at 323 RMP facilities across the U.S. The accidents caused more than $260 million in damages, which resulted in 14 fatalities, at least 330 injuries and caused more than 64,000 people to shelter in place when the chemicals leaked.

The most recent leak in Arizona happened on May 5, 2014, when a construction crew at the Intel Corporation's Ocotillo Campus plant severed a pipe containing ammonia. It exposed 12 people to the toxic gas, all of whom required on-site treatment. Two of them were later transported to local hospitals.

"The public should be greatly concerned about these facilities," said Sean Moulton, director of Open Government Policy, which is part of the Center for Effective Government, a nonprofit organization dedicated to government transparency and public access to information. "As a public, as a country, as a general population, we probably know less now and are less prepared for emergencies at these facilities than we were 15 years ago when the (Risk Management Program) started."

ABC15 and AZCIR reporters spent several months collecting and analyzing federal documents from the EPA to determine what hazards exist in and around Arizona communities and whether the necessary oversight is in place if a worst-case scenario became an actual disaster.

The RMP reporting requirements were designed to reduce chemical risks within communities surrounding these facilities and to help local fire, police and emergency response personnel to prepare for an accidental releases of the toxic and flammable chemicals.

The list of RMP chemicals is long, but it doesn't include ammonium nitrate, the chemical compound that caused the 2013 explosion in West, Texas, which killed 15 people and injured hundreds more.

ABC15 and AZCIR reporters explored sweeping shortfalls and absent regulatory oversight of ammonium nitrate in the first part of this series, which includes implications for other chemicals stored at facilities such as those identified in RMP laws.

A retail exemption exists for companies selling ammonium nitrate directly to consumers, which allows the facility to avoid chemical reporting requirements. Reporters found a similar retail exemption is in place for companies that should file Risk Management Plans.

Companies selling propane and other flammable fuels at a stationary facility, in which more than half of its income is from direct sales to consumers, are not required to file an RMP.

This flammable fuels retail exemption was added to the EPA's RMP law in 1999 through an amendment known as the Chemical Safety Information, Site Security and Fuels Regulatory Relief Act, and was designed to help companies such as gas stations from having to submit RMP documents.

Moulton said even if companies store the fuels in quantities that exceed RMP reporting requirements, they aren't required to file the emergency plans and risk assessment documents with the EPA.

"The RMP is a great first step in terms of understanding the risks in our front yard," Moulton said. "But it has a number of holes that prevent it from really giving us the full picture."

%page_break%

Public access to RMPs heavily guarded

Because of increased threats from terrorism, the act also limited public access to RMP documents. The EPA previously posted the plans online. The changes restricted public access to the Off-Site Consequence Analysis information, known as the "worst-case" scenario portion of the plan.

Now, one person can only review 10 facilities per month, in person, without any electronic recording devices, within a federal reading room, and under the supervision of federal agents.

Arizona has just two such rooms available for public access to these documents. One is in Phoenix and the other is in Flagstaff, Ariz.

"Unfortunately, in an effort to get security, we've swung too far into the realm of protecting information or withholding it," Moulton said, who advocates for public transparency with the Center for Effective Government. "We ignore the benefits of information and how it can actually help make communities safer."

But Mark Howard, the director of the Arizona Emergency Response Commission, said the security concerns for high risk facilities outweigh the benefits of full public disclosure.

This is the same approach Howard cited for protecting lists of ammonium nitrate storage facilities in the first part ofABC15 and AZCIR's investigation of hazardous materials oversight.

Howard is responsible for managing emergency plans from local and state emergency response personnel across Arizona, which includes chemical inventory lists and access to the EPA's RMP documents. He said it is up to the EPA to provide public access to RMP listings but that for the information he is able to release, he balances the business's security interests with that of the public's right to know.

"We do try to protect (the information)," Howard said. "I do want to make sure that the businesses are confident that we're going to secure their information concerning their facility.

"How is that going to serve that citizen any better to know what's there?" Howard said.

Moulton said knowing this information is an important part of emergency planning for communities and first responders.

"First, at the most fundamental level in terms of emergency management, you can't plan for an emergency if you don't know that there's a risk," Moulton said.

Information exists on the EPA's Vulnerable Zone Indicator website, which allows residents to search for RMP facilities to determine if their home is within a worst-case danger zone. The website will send an email notification to anyone searching for facilities and will inform them if an RMP facility is nearby.

The website doesn't, however, list or name the facilities in its emailed response. Instead, it forwards a link to the EPA's website which details the nearest local emergency response planning committee.

%page_break%

Arizona chemical leaks highlight need for public awareness

Risk management plan facilities are often located within the state's densest population centers. In the most extreme of Arizona's worst-case scenarios, one gaseous explosion has the potential to impact an estimated 1.9 million people.

That facility is DPC Enterprises in Glendale, Ariz. In 2003 it had a chlorine gas leak of 1,900 pounds that led to the evacuation of a 1 1/2 square mile area in Glendale and Phoenix, and required 16 people to be treated for exposure, 11 of whom were police officers. If the company's worst-case scenario incident were to happen, 180,000 pounds of chlorine would release into the air with the potential to spread 14 miles in each direction.

"By far, the most common calls here in the state are with ammonia -- anhydrous ammonia, or the gaseous form, and chlorine," said Dr. Frank LoVecchio, co-director of the Poison Control Center at Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

LoVecchio said that it would be "very, very hard for any hospital in Phoenix -- or even all of the metro Phoenix hospitals" to deal with an accident involving hundreds or thousands of patients.

In all, Arizona has 178 facilities that have filed risk management plans with the EPA. But of those, only 112 are currently active within the RMP database. The remaining facilities have deregistered, meaning the company no longer stores chemicals in the amounts that require filing, changed its chemical processing procedures to safer models, or no longer stores the chemicals at all, among other reasons.

Accidents like the 2003 leak at DPC Enterprises in Glendale, Ariz., highlight the need for public awareness of potential hazards within their neighborhoods as well as the firefighters and police officers responding to such incidents.

The U.S. Chemical Safety Board, which investigates chemical leaks across the U.S., released the findings of its investigation into the 2003 DPC Enterprises leak and found significant lapses with safety procedures at the facility and the ability of first responders to communicate during a chemical accident.

"The (2003 chemical leak) occurred over 10 years ago and has been the subject of extensive review both internally at the company and externally by the Chemical Safety Board and others," Wayne Penick, manager of safety, health and security at DPC Enterprises, stated in an email. "DPC acted swiftly to address the finding of these reviews, implemented extensive corrective actions, and has not experienced any similar accidents since."

%page_break%

Increased oversight could improve community safety

The EPA is responsible for regulating RMP compliance, which includes inspections and oversight of states such as Arizona.

"When we do an RMP inspection in Arizona or anywhere else in the region, we invite local authorities or fire department to join us," EPA spokeswoman Margot Perez-Sullivan stated in an email.

Perez-Sullivan said the EPA works closely with the Arizona State Emergency Response Commission, Local Emergency Planning Committees and emergency response personnel within the jurisdiction of RMP facilities.

Howard said his commission doesn't receive the RMP documents directly from facilities. Instead, he said, the commission has access to the database, which houses the plans. He said it's up to local emergency planning committees within each county to incorporate and plan for RMP facilities, but that the commission does review the resulting emergency plans.

"(Emergency planning) is really more at the local level than it is at my office," Howard said.

But according to the April report from the EPA's Office of Inspector General, increased federal oversight of RMP facilities that import and export hazardous chemicals could help with state and community-level emergency planning.

The report identified large shipments of anhydrous ammonia and chlorine entering U.S. ports and facilities, indicating that some facilities aren't filing RMPs as they should.

It analyzed data from hazardous material imports and found that chemicals exceeding the RMP threshold requirements are arriving at companies that haven't filed with the EPA. This includes facilities that imported more chemicals than the amounts listed on the company's current RMP.

It also found return shipments of empty containers, implying the facility either produced or stored amounts of chemicals requiring RMP reporting but didn't have such a plan on file.

Arizona is one of several states that are singled out in the report. It said one facility here received return shipments of empty anhydrous ammonia containers, which the OIG estimated could have stored 34,000-40,000 pounds of the hazardous chemical. The facility had an RMP on file, but it did not include documentation for anhydrous ammonia.

Officials from the EPA's OIG said the findings still need to be verified from the report but that the information can be useful for the RMP program to determine if shortfalls in oversight exist.

Failure to follow RMP program requirements can lead to accidental release of these toxic chemicals and "inadequate responses to protect the public when such accidents occur," the OIG report stated.

It's this risk for potential accidents, combined with the explosion in West, Texas in 2013, that prompted an executive order from President Barack Obama to improve the safety and security of chemical facilities across the U.S. It creates a national working group, which is tasked with examining current laws and to make recommendations on how to improve the safety of storing and transporting hazardous materials in the U.S. The recommendations from the group are expected early this summer.

Holly Brown with the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting contributed spatial analysis and mapping for this story.